An Ark In The Alps

Halfway up on the way to the Mont Blanc summit is where alpinism, architecture and wildlife protection meet. And we meet Isabella Vanacore Falco, the guardian of an alpine ark above Courmayeur.

It takes less than two minutes to reach the top. The glass sliding doors of the gondola lift open and you enter the middle station of the "Skyway Monte Bianco". A futuristic facility at over 2,000 m that not only houses a bar and boutique, but also a restaurant and its own cinema. And right here, halfway to the summit of Mont Blanc, it is – the alpine ark.

This ark is not a huge wooden boat and there are no exotic animals in it. What we find is a large garden with lots of plants growing on its barren soil. Alpine plants – from the most diverse mountain regions of the world, from the Andes to the Himalayas to the Urals. Here they can grow and flourish. And there is one person watching over them: Isabella Vanacore Falco. She is the director of the Saussurea Alpine Botanical Garden, the highest botanical institute in Europe. And in a way, Isabella is to the garden what Noah once was to his ark.

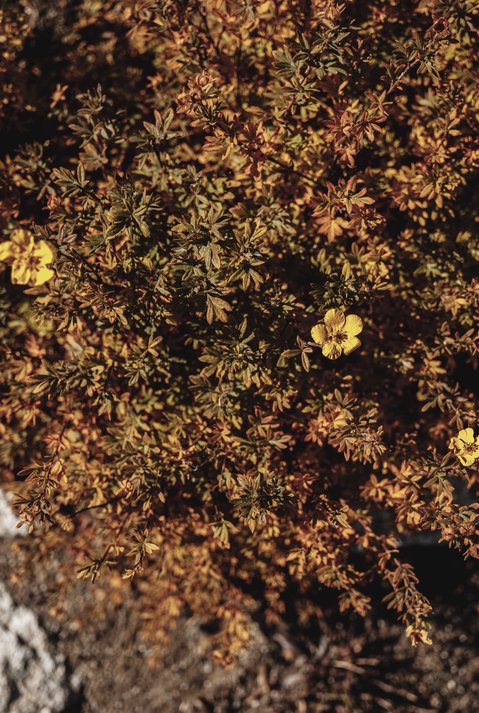

"We protect things to preserve them for the generations to come," Isabella says as we follow her along the garden's stone-flanked paths. To the left and right of the paths are plots, each of them has a different plant growing on it. Isabella pauses at a circular bed: Arnica montana reads the sign in it. A yellow-flowered mountain plant rises from the earth - beautiful, but inconspicuous. It belongs to the composite family, is native to the Alps and was once voted Flower of the Year, but more importantly, it is a protected plant, "just like many other plants in our garden". And that is exactly why Isabella is here.

You might think that Isabella came to Courmayeur for the high peaks of the Mont Blanc massif or the valley’s magnificent nature. But it was science that brought the young student from Turin here over 20 years ago. An excursion to the Saussurea Alpine Botanical Garden, a research project in Val Ferres and a doctorate in botany later, Isabella decides to stay. "Because I don't want them to get lost," says Isabella, and by "them" she means the plants - her babies.

"Every time we plant a new seed in the garden and a young plant sprouts from the earth, it's like the birth of a new life." Life for which Isabella feels responsible. She nurtures and cares for her more than 900 different offspring, even plays them music over the garden's sound system. "Classical music. Their favourite is Vivaldi's Symphony of the Four Seasons," and what may sound like esoteric humbug at first is scientifically proven reality: acoustic playback has led to faster growth and more pronounced flowering in alpine plants. Isabella grins because she is used to incredulous looks. Not all visitors believes her story, but she has another one for those. And we follow her a few steps further through the garden.

Isabella bends down to a plant: at the base of its stem, elliptical-shaped green leaves spread out to the sides, while white petals, densely arranged, grow upwards. "This one is said to have been Alexander the Great's downfall," she says. Once again she recognises doubt in our eyes, for what we don't know is that White Germer, the name of the highly poisonous plant, was used in ancient times as an herbal emetic. "Too high a dosage, however, can lead to death," Doctor Isabella explains, "and the symptoms of Alexander the Great's illness according to historical accounts suggest poisoning by this plant." Not conclusive proof of the Greek general's mysterious demise, but of Isabella's encyclopaedic knowledge of the life of every plant in the garden. One need only pay her a visit.

After we have finished our round through the garden and learned a lot about the world of alpine plants, it’s time to ask one final question: What’s going on around here when winter comes and everything is covered in snow? "Then I work in the archives and raise new seeds," Isabella says dryly. We had expected a better story, but she adds: "This is all about preserving the garden and all its diversity for those coming after us”. This is what drives her. Just like Noah on his ark saving what the great flood would otherwise have taken with it. Isabella is not protecting her children from an apocalyptical natural disaster, but from a much greater threat: man himself.

Text: Robert Maruna // friendship.is

Photos: Ian Ehm // friendship.is

April 9, 2022